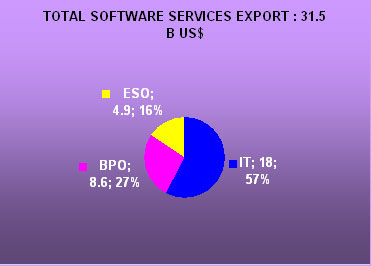

India is really emerging as a design outsourcing hub. Engineering Services Outsourcing (ESO) contributed 16% of India’s total software services export revenue in the year 2006-07. IT Industry still continues its supremacy with 18 Billion US$, followed by ITES (8.6 Billion) and ESO (4.9 Billion). NASSCOM predicts ESO to equal its share to ITES by the end of 2010.

Even as Indian vendors continue to move from strength to strength as providers of Information Technology Outsourcing (ITO) and Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) services to companies around the world, the possibility now exists for India to add a third major services growth stream - Engineering Services Outsourcing (ESO) - to its rapidly evolving economy.

Engineering services is a huge market: Global spending for engineering services is currently estimated at $750 billion per year, an amount nearly equal to India’s entire gross domestic product. By 2020, the worldwide spend on engineering services is expected to increase to more than $1 trillion.

Of the $750 billion spent today, only $10-15 billion is currently being offshored - a tiny fraction of the total. India brings home about 12 percent of today’s offshored market, which it currently shares with Canada, China, Mexico, and Eastern Europe. By 2020 as much as 25 to 30 percent of a much larger $150 to $225 billion market for offshored engineering services could belong to India - as much as $50 billion in annual revenue-if the country builds the capacities, capabilities, infrastructure, and the international reputation it needs to become the preferred destination for these complex, high-value services.

India’s Value Proposition: Advantages

India possesses some formidable strength as a potential powerhouse of engineering services. At the top of the list is the widespread availability of highly skilled, English speaking engineers. At present, India accounts for 28 percent of all of the available ESO and BPO talent in low-cost countries. The strong track record of Indian vendors in BPO and ITO is also likely to boost the confidence of would-be global clients in India’s capabilities. A third positive factor for India is the fact that many of the vendors who will evolve into engineering services providers are likely to already have a great deal of experience winning and retaining BPO and ITO contracts. The delivery models are well established, and after a decade or more in business, these vendors are likely to have developed the ability to maintain a very high level of quality control. India has the potential to control 20 to 25 percent of the global market for offshored engineering services by 2010. Of India’s total market share in offshored engineering services, High-Tech/Telecom will likely represent the largest slice, capitalizing on India’s existing relationships and expertise. Automotive will most likely be the second-largest sector. Construction/ Industrial, Aerospace, and Utilities vendors, on the other hand, are all relative youngsters, with averages of five years’, five years’, and four years’ experience respectively. As might be expected in such a burgeoning market, the engineers who work for vendors in the ESO industry have only a few years’ experience. Right now, the average level of work experience for individual engineers is less than 5 years, across all five sectors. Given the rapid expansion of the Indian economy, it is unlikely that these numbers will change appreciably any time soon

Beyond the capacities of individual firms, India’s growing economic clout is also expected to act as an increasingly attractive lure for many global companies. The Economist Intelligence Unit forecasts that by 2015, India’s GDP is likely to have grown to 2.5 times its current size, with a strong emphasis on personal consumption - a boon for consumer products companies. This trend may prove to be a powerful additional incentive for potential ESO clients to use Indian engineering services as a way to increase their presence in and knowledge of the Indian market.

India’s Value Proposition: Challenges

At the same time, India faces substantial challenges as well. The most crucial challenge, perhaps, is the cultivation of talent. Right now, approximately 35,000 engineers work in engineering services. By 2020, India could need as many as 250,000 to truly reach its potential in terms of market share. While India is already the largest producer of engineers suitable for BPO and ESO outsourcing among other low wage countries, it will not have enough trained professionals to handle the projected volume of work as the ESO space develops. Although India has almost 1,400 engineering schools, only a handful of schools are recognized as providing a world-class engineering education. Unlike BPO, where the primary requirement is English-speaking capability, engineering services calls for candidates with a good grasp of engineering fundamentals. Effectively, this means that the number of graduates suitable for ESO work today is actually a small percentage of today’s 220,000 graduating engineers.

Infrastructure is another key issue. While the IT infrastructure is adequate for current needs, India still lags other key Asian countries in most respects. In speed and cost of Internet access, road infrastructure, port infrastructure, air infrastructure, and telecom infrastructure, Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore are all still ahead of the game. In fact, of those five types of essential infrastructure, only India’s telecom infrastructure can be considered adequate. Perhaps more significantly, India also lags behind China in such metrics as roads, airports, and telecom infrastructure - all of which may be of crucial importance as China is likely to become India’s main competitor for this business.

Competition for Offshored Engineering Services

A key consideration for India in its bid to become the dominant player in offshored engineering services is its competition from other low-cost countries. Within the developing world, a number of countries are likely to participate in the growth of ESO. Participants who can provide low-end services are likely to include small countries unfamiliar to players in the BPO markets, such as Nigeria and Vietnam. When it comes to high-end, complex tasks, however, the most likely scenario is that India and China will bring home the most contracts, since there are very few countries that can pose a threat, given their lack of scale relative to India and China.

China is likely to be a formidable competitor for India: While India has the advantage in terms of English language skills, cultural compatibility with the West, a robust political and legal system, and relatively strong protection of intellectual property (IP), China has a much stronger infrastructure and a well-developed manufacturing base.

“Go Get Forty!”

India has a number of options at this point in terms of how to strategically address its growth. Capturing $40 billion of the world’s offshored engineering business would require a concerted effort of business and government almost without precedent in India, but long familiar to many fast-growing Asian markets, such as Singapore. To get there, stakeholders in India, from within the business community and elsewhere, will need to take five key steps to make India an attractive, viable destination for engineering services.

1. Build an “Engineered in India” brand name.

A concerted marketing effort to build awareness of Indian engineering expertise could multiply opportunities for Indian ESO firms. Beyond the work that NASSCOM is doing, a separate trade organization or group within NASSCOM dedicated to the promotion of Indian engineering could help elevate global recognition of India’s engineering capabilities. Such a group would create trade shows, and establish outreach offices in key markets around the world, such as San

Francisco, Stuttgart, Detroit, Paris and Tokyo.

2. Improve domain expertise.

Unlike previous ventures in capturing global services, good general skills will not be enough to capture the attention of companies looking to outsource high-value, mission-critical engineering projects. Domain expertise could be gained first by trading expertise for at-cost services. Key acquisitions of some leading foreign design shops could enhance knowledge while providing firms with access to ready-made client relationships. Hiring top engineers from outside the country could also improve vendors’ abilities and enhance their cultural compatibility with key countries.

3. Focus on the creation of infrastructure

Overcoming India’s current infrastructure challenges is the work of generations. However, when it comes to ESO, India doesn’t have that much time. India should take a tiered approach to infrastructure development, and emphasize the modernization of infrastructure in a few key cities

To put it in perspective, Bangalore currently generates $6 billion annually in ITO/ BPO revenue, compared to Chennai, Hyderabad, and Mumbai, which yield $6 billion in such revenues combined. If the $40-50 billion industry that India is aiming for in engineering services materializes, it will require five to seven or even more “Bangaloreclass” cities - urban areas that equal Bangalore in terms of infrastructure and office space.

4. Improve the workforce in terms of quality and quantity

Even if India is able to position itself as an attractive destination for engineering services, the country will only capture a limited amount of business if it lacks enough engineers to fulfill the contracts. Toward that end, a vast new investment in engineering education must be made to position India to take its full potential share of the ESO business. Quality needs to improve at the same time as the quantity. Curricula must be upgraded to international standards at many schools, if students are to have the right skills to serve in this market, and standardized, in order to increase the number of “market-ready” graduates. Certification program standardization would play a role in this regard as well, by pushing institutions to think more about helping their students succeed in the marketplace. At the same time, adding 12-month training programs onto current educational requirements, in the form of advanced internships similar to a medical residency, could help leverage existing expertise.

6. Leverage local business and local demand.

One other area in which the government could play a positive role is in taking a structured approach to providing incentives to multinationals wishing to create or expand their engineering presence in India. The temptation for local governments to compete in trying to attract major ESO clients will be strong. While such competition has its place, better results would be gained through a somewhat more structured program that leverages existing local industry strengths. Offset programs, for example, could leverage large imports in Aerospace, Defense, and Utilities. Such programs could be offered as a set-off against export commitments that players are unable to meet. For example, Indian arms of international OEMs unable to meet their export commitments could offset engineering services to Indian vendors against those commitments. To maximize their impact, such programs would need to ensure that business flows to the right area, by specifying, for example, the particular sector to which it should flow. At the same time, the desire of international companies to play in the Indian market should not be underestimated. India has one of the fastest-growing consumer markets in the world, right after China, and foreign companies’ desire for greater access could be a powerful tool for growing local business.

Conclusion

The opportunity for engineering services offshoring in India is vast. Particularly in those industries where it is most advanced, India has little time before other countries make more inroads into the market. In Automotive, for instance, only three to five years remain before multinationals begin looking for global partners in developing their high-end engineering projects. As with any market, the ESO market is going to become progressively more difficult to break into over time, particularly as cost is unlikely to be the most important factor in sourcing a project design. That is good news for the countries that capture that market early and keep it, and not so good for those that wait for the market to mature.

Finally, it should be noted that the stakes for India are even higher than the loss of one potential market. Current service relationships in BPO and ITO could well be impacted if India fails to help its engineers further ascend the value chain. If BPO and ITO are seen merely as cost-saving commodities, sooner or later, outsourcers will look elsewhere for a lower price. To maintain their current, hard-won relationships, vendors will need to add more value - the kind of value that a mature engineering services provider will be able to offer.